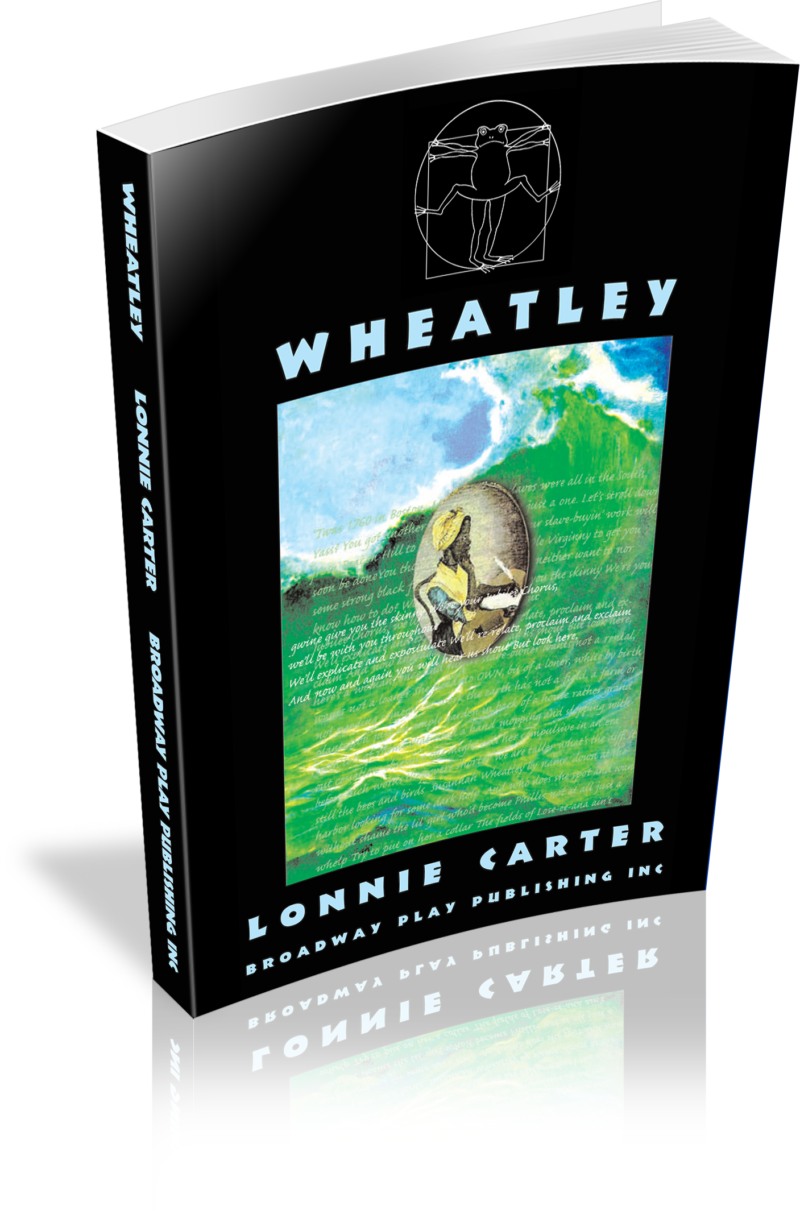

Wheatley

Description

The real life, storybook adventures of Phillis Wheatley; a revolutionary American slave girl, whose poetic genius lifted her from New England parlor trick into the great salons of Europe and beyond. Follow her travels with the Countess Selena, Ben Franklin, and the Admiralty from Boston to London and back, where she will find love in the arms of Samson Osee Power Frock — free man of color.

Production Info

Full Length Drama (about 90 minutes)

Minimal Set Requirements

Period Costumes

Press Quotes

“WOW! … a comic-book exclamation may be the only word left in the wake of the grand torrent of language, movement and sublime imagination on display in this world premiere … What a sense of awe and astonishment is generated by this ninety-minute fantasia on the life and legacy of Phillis Wheatley, the African American poet who became a literary celebrity in the era of the American Revolution — and the first of her race to be published in this country. And what a profound and intriguing story it tells about race and art in America, and about the singular nature of creative genius … Never heard of Wheatley? Neither had I. So here’s the one-minute version of her life: She was born in Senegal in 1753, brought to the Boston slave market at age seven and purchased by the well-to-do businessman John Wheatley at the urging of his wife, Susannah, who took a fancy to her beauty and spirit. From the start she was a slave, and wasn’t a slave — a girl set apart, who was taught to read and write, was exposed to Greek and Latin and the Bible, and easily fell under the spell of a preacher’s orations. Wheatley’s first poem was published in 1767. A collection of her work was issued six years later in London. And for a brief time she became all the rage there, meeting the swells of society and, not incidentally, making the acquaintance of Benjamin Franklin. But society ultimately grew bored with and skeptical of her, and the poet made her ‘second passage’ to America, falling in love, having children and worrying that her poetic gift might be lost. By the age of thirty-one she was dead, though, as Carter suggests, something of her voice echoes down through the centuries, informing everything from the blues and jazz to the scratchin’ of a hip-hop D J. Lonnie Carter is the polymorphous Victory Gardens wordsmith who last season gave us THE ROMANCE OF MAGNO RUBIO. Part James Joyce, part John Coltrane, part Diddy, he often is mistaken for African American, but is a white writer fascinated with the way English has been reshaped by black culture. Carter’s WHEATLEY is no docudrama; it is in fact spun into pure invention that comes out in the form of a richer truth. (The play’s riff on globalization should be performed at the next World Bank get-together.) The same is true of Scruggs’ superb direction, which employs a slew of deft theatrical tricks and taps the talent of a quartet of actors who must have had nightmares while learning Carter’s dense, tongue-twisting, mind-bending text …” —Hedy Weiss, The Chicago Sun-Times

Author

Lonnie Carter

Lonnie CarterLonnie Carter's play THE ROMANCE OF MAGNO RUBIO received eight Obies for its production by the Ma-Yi Theatre Company in 2003. His plays have been produced by The Yale Repertory Theater, the American Place Theater, Victory Gardens Theater, the Long Wharf Theater, and at the first Asian-American Theater Festival in New York City (2007), the Los Angeles Theater Center's Latino Theater Festival (also 2007) and festivals abroad (the Philippines and Romania). His plays include CHINA CALLS, THE SOVEREIGN STATE OF BOOGEDY BOOGEDY, THE GULLIVER PLAYS (LEMUEL, GULLIVER, AND GULLIVER REDUX, published by Broadway Play Publishing), BABY GLO, WHEATLEY (the Colonial HippeHoppe story of Phillis Wheatley), CONCERTO CHICAGO, and most recently THE LOST BOYS OF SUDAN, produced by the Children's Theatre Company in Minneapolis (Tony Winner for Best Regional Theatre 2003). THE LOST BOYS (AND GIRL) OF SUDAN was produced by Victory Gardens in 2010. He is a charter member of the Victory Gardens Playwrights' Ensemble. (Victory Gardens was the Tony Winner for Best Regional Theatre 2001). He is an Alumnus of New Dramatists in New York and the Playwrights' Center in Minneapolis. He is a graduate of the Yale School of Drama and Marquette University, a Guggenheim Fellow and twice a Fellow of the National Endowment of the Arts and the Connecticut Commission on the Arts. He has taught at the Yale School of Drama, the Hammerstein Theater Center at Columbia University and the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. His screenplay for THE ROMANCE OF MAGNO RUBIO is in pre-production.

Book Information

| Publisher | BPPI |

|---|---|

| Publication Date | 10/1/2005 |

| Pages | 54 |

| ISBN | 9780881452792 |

Special Notes

by special arrangement with Broadway Play Publishing Inc, NYC

www.broadwayplaypublishing.com